Developing Cities in Turkey and the Challenges for the Turkish Economy in the Next Decade

Utku Balaban, Associate Professor of Sociology at Labor Economics and Industrial Relations, Ankara University and European Commission Marie Curie Grant Fellow

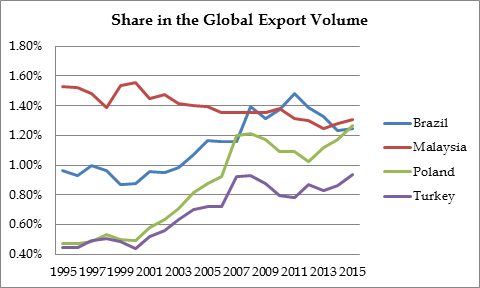

Turkey is the most industrialized country in the Muslim Middle East. In 2014, the Turkish economy produced almost three times as much industrial value added as Egypt and Iran did, both of which have roughly the same population as Turkey. Furthermore, Turkey increased its share in global exports by a factor of two during the 2000s. More than 95 percent of the Turkish exports are manufacturing goods. Turkey had similar growth rhythms as other emerging economies such as Brazil, Malaysia, and Poland. Thus, it is one of the key emerging economies in the Middle East.

Source: UN Comtrade

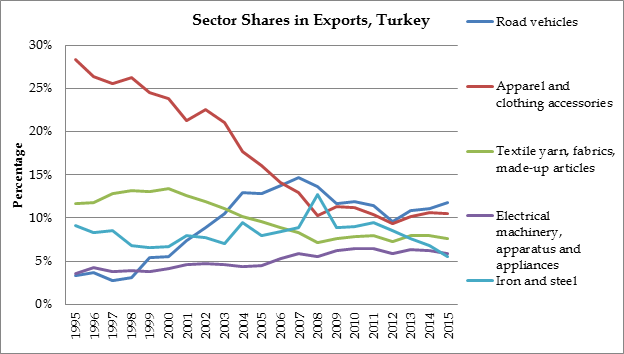

One of the major factors that led to the growth of the Turkish manufacturing exports in the 2000s is Turkey’s NAFTA-like Customs Union Agreement with the EU ratified in 1996. This agreement had a major impact on the country’s automotive industry. This sector grew at a phenomenal rate in the late 1990s thanks to the investment by major car manufacturers such as Ford, Toyota, and Hyundai. Similarly, machinery and appliance production expanded within the same decade. Both sectors grew at the expense of the garment and the textile industries that characterized Turkey’s late industrialization in the 1980s.

Source: UN Comtrade

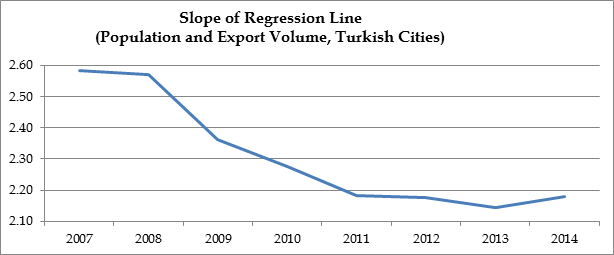

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute and Turkish Exporters’ Assembly

In fact, the last decade witnessed a weakening relationship between the population size and the export volume for individual cities in Turkey. One particular factor behind this regional development dynamic is the relative industrial decline of Istanbul, the economic capital of Turkey. Between 2004 and 2013, Istanbul’s share in Turkey’s export volume decreased from 57 percent to 45 percent. This megalopolis is still “the (industrial) outlier” of Turkey, because it accounts for 18 percent of the nation’s population only. Nevertheless, the 2000s witnessed a wave of domestic outsourcing particularly from Istanbul to the developing cities in Turkey such as Denizli, Gaziantep, and Kayseri. In fact, Turkey succeeded in catching up with other emerging economies thanks to the industrial growth of its developing cities. Thus, the sustainability of Turkey’s economic growth very much depends on the growth of these non-metropolitan cities.

However, there are particular challenges ahead of these cities with regard to their industrial landscape. The relative decline of the garment sector and the like appears as the most urgent one of those challenges, because the gradual shift from such sectors to the energy- and resource-based sectors such as basic metals has not been coupled with a similar growth of the high-technology sectors. For instance, Gaziantep is one of these developing cities that increased its export volume ten times within the last decade. Carpet sector is the largest exporter sector in this city. However, almost unexceptionally all of the carpet looms are bought from a Belgian firm that dominates the global market. Because Gaziantep dominates the global carpet market, the entire carpet industry in Gaziantep is in effect the subsidiary of the Belgian loom producer. In the absence of such backward linkages, the SMEs in this city operate with high debt-to-asset ratio and have on average short business longevity.

Another and probably more important challenge is political instability. Turkey currently faces two major security threats. First, the country has become a target for ISIS for the last two years. For instance, a suicide bomber killed 107 people on October 10, 2015 during a peace demonstration in Ankara. Second, a junta attempted a coup d’Etat in July 2016. The government pointed to a masonic network led by Fethullah Gülen, a religious leader, as the culprit behind this putsch.

This political context in Turkey disrupts the business climate in the developing cities. For instance, Kayseri ranks the third in Turkey’s manufacturing output among the cities that do not benefit from the spillover effects of the metropolitan areas. This city is also the largest non-metropolitan furniture producer. However, the largest furniture company of the city was confiscated in September 2016, because company owners were accused of supporting the failed coup in July 2016. Gaziantep is another example of how the domestic and international political turmoil jeopardizes the Turkish economy. Gaziantep’s geographical proximity to Iraq and Syria was essential in its high performance during the 2000s. This geographical advantage now poses a major threat to the security of Gaziantep’s industrial production. Along with the inflow of more than 300,000 Syrian refugees to the city, who account for roughly ten percent of this city’s population now, the ISIS militants killed scores of people in a number of suicide bombings in recent months and the ISIS leaders threatened Gaziantep as one of their three main targets in Turkey. Furthermore, the second largest corporation of the city was confiscated in October 2016 for the same reasons as the aforementioned furniture conglomerate in Kayseri.

Unless immediate measures are taken to stabilize the politics in Turkey, the economy remains vulnerable to two interrelated risks. The first and bad one is the economic depression in developing cities because of the aforementioned security threats. This path could stall the already slow Turkish economy. The second and worse scenario is the further destabilization of the country, which would certainly lead to capital flight from the economy. After both S&P and Moody’s recently downgraded Turkey’s credit rating, the Turkish currency already began to depreciate against the US dollar last month. Even though this will likely to affect the export volume by labor-intensive sectors positively, the aforementioned shift to the resource- and energy-intensive sectors make the Turkish companies more vulnerable to such ups and downs of the domestic currency. Depending on which one of these paths will be taken in Turkey, its success story in the 2000s will be likely rewritten in coming years.