Fed rate hike: What’s next for emerging markets?

The first rate rise in nearly a decade happened mid-December 2015. Fed raised interest rates by 0.25%, given the U.S. economic outlook. But what does this rate rise mean for emerging economies?

The first rate rise in nearly a decade happened mid-December 2015. Fed raised interest rates by 0.25%, given the U.S. economic outlook. But what does this rate rise mean for emerging economies?

by Michael Aiyetan, MBA ’16, EMI Fellow

There are two key factors that could make higher U.S. interest rates difficult for emerging markets (EM). First, rate rise could lead to reversal of capital flows. That is, a rise in investment returns in the United States would make international capital to drift away from emerging market countries. Second, rate rise could lead to higher debt service cost.

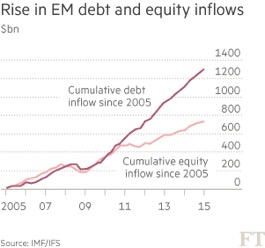

Following the global financial crisis, investors flocked to EM equities and debt, amid low rates and low growth in developed markets. These capital movements were mainly encouraged by the sustained decline in interest rates in the U.S. The lower interest rates attracted the investors to the high yields offered by the emerging economies. Investors reached for yield without an appropriate appreciation of risk. But, as Fed now begins to slowly increase rates, investors may continue (i.e. they have already started as they anticipate the rate hike) to reallocate portfolios away from the riskier EM assets and back toward the United States, where there is better growth prospects, rising yields (though from very low levels), and greater safety. This could be really challenging for some EM countries that have relied on external flows to finance their most recent economic growth.

The IMF estimates that emerging markets have borrowed trillions of dollars more than commodity prices and global demand warrant. Many governments and corporations in EMs took advantage of low cost dollar finance, issuing bonds denominated in U.S. dollars and amassing debt that amounts to around 160 per cent of GDP. Without a shred of doubt, a rate rise would make it more expensive for the EM borrowers to service their debt commitments. It would spell deeper pain for the countries that have borrowed heavily in the U.S. currency. Even though much of that debt was borrowed by companies, shocks to the corporate sector could quickly extend to the financial sector and pervade public finances.

Apparently, the Fed rate hike does not come at a great time for EM. It came while emerging economies are experiencing serious economic woes, such as spillover effect of China’s slowdown, commodity crash, weakening currencies and so on. The rate hike could worsen the situation, and even help spark a full-blown crisis. Thankfully, the Fed assured that rate will move in “gradual” step and is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. Therefore, it is possible that this gradual rate rise would be a smooth sailing for emerging markets, if they can really focus their monetary and fiscal policies on reducing vulnerabilities.